As great power rivalry intensifies in recent years, South Korea recognises the salient need to diversify its diplomacy to avoid being caught in the US-China crossfire. Conventionally, Korea’s foreign policy focuses primarily on the four main powers – US, China, Japan and Russia. In a bid to hedge against growing US-China competition and to expand strategic autonomy, Korea conceived a two-pronged plan called the New Northern Policy (NNP) and New Southern Policy (NSP). The former aims to strengthen Korea’s relations with Russia, Mongolia and countries in Central Asia whilst the NSP intends to deepen relations with ASEAN and India. The NSP delineated numerous initiatives and key areas of cooperation subsumed under the three main pillars of peace, prosperity and people. Essentially, the NSP aspires to enhance economic cooperation with ASEAN countries and India, primarily through development projects. The NSP has also been recently refined to become NSP Plus, to include the changing priorities precipitated by Covid-19 such as post-pandemic recovery and global health, amongst others.

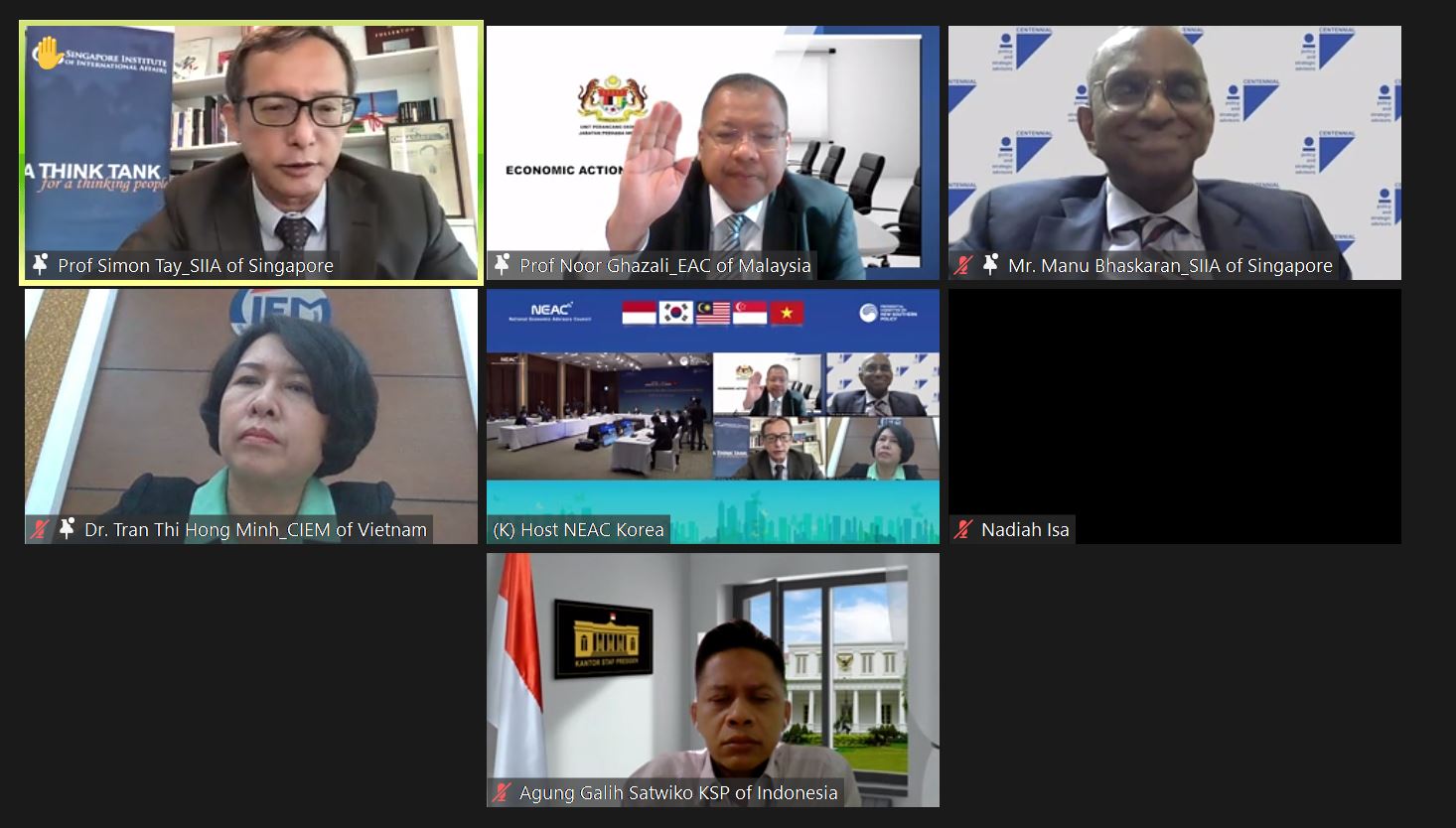

On Thursday, 14 October 2021, the National Economic Advisory Council (NEAC) of Korea inaugurated the Conference of the Asian Council of Economic Policy (ACEP). ACEP aims to build upon the NSP and NSP Plus enacted by the Korean government through providing a platform for ASEAN countries and Korea to convene and devise solutions to address common challenges. The common problems range from socio-economic impacts caused by the pandemic to climate change issues.

In his opening address, Prof Simon Tay underscored the importance of solidifying cooperation amongst Asian countries amidst US-China rivalry and committing to global trade and international rules-based order. Prof Tay highlighted two main areas requiring urgent attention, green recovery and digitalisation. As countries rebound economically, it is crucial to ensure that the economic recovery is sustainable with low carbon emissions. A viable approach in facilitating post-pandemic green recovery is green financing. The pandemic has also expedited digital transformation as the ASEAN market saw a 63% increase in e-commerce as compared to 2019. Hence, a robust digital infrastructure comprising more aligned and interoperable rules, policies and standards with ASEAN and Korea must be in place to leverage on the uptick in online businesses.

For the first panel, “Post-Covid-19 Challenges, Policy Responses, and Regional Cooperation in Asia”, speakers from Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and Korea shared the economic challenges their respective countries grappled with, and the solutions to resolve such economic setbacks. The need for reforms in building resilient economies that can withstand future crises and shocks is a common theme undergirding the four countries’ recovery plans. Panellists included Mr Manu Bhaskaran, SIIA council member and CEO of Centennial Asia Advisors Pte Ltd, Singapore; Prof Noor Ghazali, Executive Director of the Economic Action Council, Malaysia; Dr Tran Thi Hong Minh, President of the Central Institute of Economic Management, Vietnam; and Prof Kang Moon-sung, NEAC Council Member and Professor of International Studies at ChungAng University. The session was moderated by Prof Chun Sun Eae, NEAC Council Member and Dean of Graduate School of International Studies at ChungAng University.

Challenges to globalisation

A major concern for trade-oriented and open economies is the phenomenon of ‘slowbalisation’ that is taking root today. As opposed to deglobalisation, slowbalisation refers to the significant slowing down of flows, where benefits arising from global supply chains will not grow as much as before. This can be attributed to several contributory factors. Firstly, the global trend of growing protectionism, as evidently exhibited by the major superpowers US and China. The US is turning inwards to focus on the middle-class and industry policies whilst China has announced its 2025 Made in China strategy to reduce its reliance on foreign technology and instead, plans to invest heavily in its own innovations to boost the domestic and international competitiveness of Chinese companies. Next, the openness of countries to trade has also inevitably left large segments of population far behind, widening the income disparity. Third, there has been escalating resistance against flows of people as populist movements across the world play on the detrimental effects of migration, undermining globalisation. Lastly, large-scale and highly integrated countries like the US and China stand as biggest winners when it comes to deploying technologies to maximise output, whilst less developed countries struggle to procure and incorporate efficient technologies, hence lagging behind.

How the region can respond?

Although countries are increasingly turning inwards and abandoning multilateralism, Mr Bhaskaran stressed that the region must “seek protection from protectionism”. Apart from relying solely on the World Trade Organisation for multilateral trade efforts, countries should engage in regional initiatives like Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to maintain trade opening. Countries who show interest in joining CPTPP but have yet to fulfill certain requirements should look into forming an informal grouping or association that is partially aligned with the CPTPP. Another means of fostering deeper economic partnership is to employ minilateralism where countries pursue smaller-scale and bite-sized cooperation on common issues that afflict the specific countries. This is illustrated by countries like Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos that work together to build transport and infrastructure links to promote connectivity and integration within the Mekong region. Hence, countries need to strengthen their domestic economy to weather the volatility of the external environment and this is only possible if countries commit to collective action.