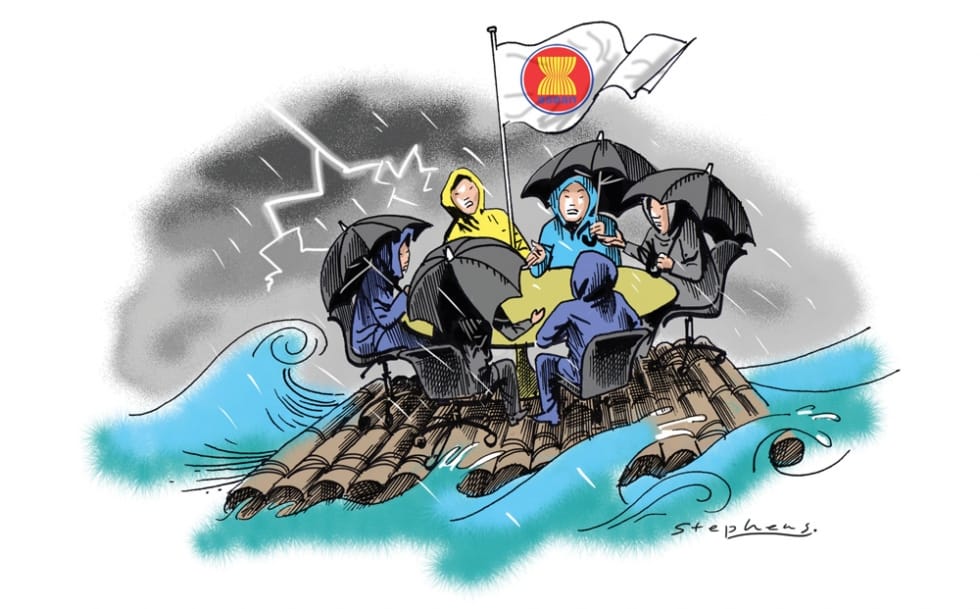

When leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations gathered this week in Myanmar, the weather forecast was for high temperatures combined with a chance of storms. The political atmosphere proved similar, with lightning-rod issues converging on the regional group’s first summit of the year.

South China Sea disputes demanded attention, with strained relations between China and some Asean members coming to the boil amid new developments. Just days before the summit, Vietnam and China traded accusations over ships being rammed as Beijing put in place a rig to begin drilling for oil. The Philippines, meanwhile, arrested 11 Chinese nationals for illegal fishing, even while China continued to demand their release.

Other Asean members face domestic problems, most visibly Thailand. The kingdom was represented only by a deputy caretaker premier, Phongthep Thepkanjana, following the constitutional court’s decision last week to remove prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra and nine other ministers on charges of abusing power.

What can Asean do in disputes involving China? In face of some members’ domestic problems, can Asean progress to be a community? How could Myanmar, chairing the group for the first time, cope?

On the South China Sea, Vietnam’s prime minister, Nguyen Tan Dung, claimed China had committed “dangerous and serious violations”. Manila also issues complaints about China. No one contradicted these voices, but without Beijing present, the group declined to judge the issue, in the interests of fairness.

Realistically, the summit could never have expected to do anything more. The much more modest aim was to avoid a disaster akin to events two years ago when the then chair, Cambodia, appeared to favour China and the meeting ended in an impasse. Avoiding a repeat could not be taken for granted, however.

After all, Myanmar is not only chairing the grouping for the first time; it also maintains a close relationship with Beijing. Even as the country has opened up to others, including the US, the Chinese presence is strong in the economy and a permanent factor because of their long, shared border.

Against this background, it is positive that, rather than a deafening silence, a statement was agreed that highlighted “serious concerns” in the South China Sea and called for restraint – without, however, taking sides. After all, some Asean claimants have in the past taken steps to begin exploration for resources.

In this context, Asean and its current chair have done the right, if discreet, thing to address the issue while maintaining neutrality and an even-handed leadership.

Fairness and discretion were also evident in approaching the situation in Thailand. In the past, the group would usually have avoided commenting on such an issue, under the principle of non-interference in matters of domestic politics. But as Asean moves towards becoming a community, there is a need for such issues to be addressed.

Yet while Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen proposed a statement by leaders, in the end only Asean foreign ministers issued one. Moreover, it was non-partisan in expressing full support for dialogue, democratic principles and the rule of law in dealing with the challenges in Thailand.

Again, this was something of a challenge for the group, especially given that the Hun Sen government has previously sided with former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra and is itself facing similar street protests challenging its legitimacy. Again, a middle path seems to have prevailed, with Asean neither falling into silence, nor allowing any one side to capture the regional voice.

This may not seem like much. But on such issues, even the great powers cannot command outcomes. Indeed, while US President Barack Obama recently swung through the region to give security assurances, this has not prevented the recent maritime contentions.

In this context, some may reckon that a group made up of merely middle to smaller countries is wise to preserve its role and credibility, even at the cost of curbing ambition. Asean is weathering, rather than seeking to control, these storms.

For areas of ambition, one should look instead to the group’s own agenda. The summit focused on the timely realisation of the Asean Community by 2015 and strengthening the group’s institutions and decision-making processes. Behind this technical and bureaucratic language is an effort to position the group as more unified and decisive in the future.

While not grabbing the headlines, the group has also considered ways to move ahead on negotiations with China on a number of issues. This involves not only the code of conduct regarding behaviour at sea, but also on broader economic cooperation. Progress with the group’s economic community is also key to its continued competitiveness and relevance to the region in business as well as politics.

There are items on the agenda where Asean can and should make progress. There are also controversies and storms beyond its control that must simply be weathered. The wisdom of this summit, the first hosted by Myanmar, was to try to judge which was which.

Simon Tay is chairman of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs and also teaches international law at the National University of Singapore. This article was originally published in the South China Morning Post on Tuesday 13 May under the title ‘Riding out the storm’. The article was also published in TODAY and The Nation (Thailand) on Thursday 15 May.

Image credit: South China Morning Post