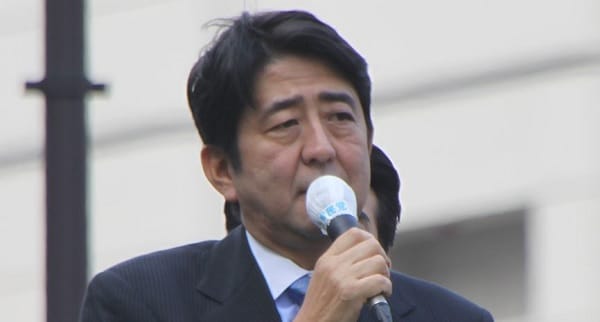

At last week’s Shangri-La Dialogue, the annual defence forum for Asia held in Singapore, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe sent a firm signal: he wants Japan to take a more expansive role in the region’s security architecture. He hopes to set the wheels in motion at the East Asia Summit (EAS) in November this year, calling for the renewal of the summit as the “premier forum” for regional politics and security in Asia. He believes that Japan and its ally the United States are well-poised to bolster security cooperation with members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Mr Abe proposed that the EAS, attended by heads of governments of ASEAN countries, China, Japan, South Korea, India, the US, Russia, Australia and New Zealand, should establish a permanent committee of ASEAN representatives, and create ties with the ASEAN Regional Forum and the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting-Plus. As a first order of business, Mr Abe wants EAS members to disclose their military budgets to enable cross-checking and promote transparency – a move clearly targeted at China.

Wishful thinking or strategic posturing?

Through this proposal, Mr Abe has made a shrewd move in countering China, which is almost certainly not willing to end the opacity over its military budget. Even if Mr Abe’s plans for the EAS never come to fruition, Japan would have already won the moral high ground over China. With Beijing then being perceived as uncooperative and secretive, the Philippines and Vietnam, the two ASEAN countries increasingly at conflict with China, would be vindicated by their claims of a growing “China threat”.

Nonetheless the Japanese prime minister’s proposals for renewing the EAS warrant deeper examination. The EAS discusses informally on areas such as energy and environment, finance, education, natural disaster management, pandemics and connectivity – too broad and wide-ranging for any meaningful discussion to take place, as critics point out. Mr Abe’s push for a “premier forum” for regional politics and security thus sharpens the raison d’être for the EAS.

But by taking up the agenda of defence spending transparency, the EAS would likely turn into an arena for contestation between China, Japan and the US – thereby driving the EAS away from its the principle of ASEAN centrality. This means that ASEAN would then be overridden by great power rivalry in the EAS, which it has sought to avoid all along sought to avoid.

The very reason the EAS was made possible was due to ASEAN’s characteristic as a non-threatening actor. That meant ASEAN had the influence to convene the other countries in the region to form the EAS – something that a polarising actor like China or Japan would not be able to achieve. So instead of the EAS becoming the region’s “premier forum”, it might simply disintegrate altogether if China decides to quit the EAS if it feels unfairly targeted by the issue of military budgets.

History may offer some relevant lessons here. The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), a multilateral military alliance supported by the United States, was created in 1954 to prevent further communist gains in Southeast Asia. This defence pact eventually failed due to lack of participation from member countries and the absence of Asian members.

Thus, Mr Abe’s push to bring defence and security issues to the forefront of the EAS’s cooperative framework may pose challenging consequences to ASEAN’s future.

Sources:

Keynote Address: Shinzo Abe [Shangri-La Dialogue – The IISS Asia Security Summit, 30 May 2014]

Shangri-La dialogue: Japan PM Abe urges security role [BBC News, 30 May 2014]